- Home

Croisi Moments: Mekong | Tonlé Sap

Tonlé Sap

In this amphibious world, where water governs over humans and their destiny, where the river is full of mystical forces, boats have eyes. Two colourful circles painted on the sides ward off bad luck. “Mainly to ensure a good catch”, adds Chhayavong, our guide. Fishing is Tonlé Sap’s gift, supplying more than 80% of the animal protein consumed in villages and representing 70% of their revenues. It guarantees the survival of this biosphere reserve listed at the UNESCO for its ecological, economic, social and cultural value. Tonlé Sap, the cradle of Khmer civilisation and Angkor’s Empire. A natural masterpiece, a feeding reserve for an entire population. Welcome to the mythical kingdom of Naga, the 7-headed snake, guardian of these sacred waters.

After Kampong Chhnang, the river is narrower before it suddenly becomes wider, in order to turn into an immense freshwater lake, the largest in Southeast Asia. It is the theater of a natural phenomenon unique in the world known as the reversal of the flow of the Tonlé Sap River: every year at the time of the monsoon, the overflowing Mekong floods Tonlé Sap, reversing the flow of the river and inundating the lake, whose size becomes four times bigger, more than 3,861 sq mi, the equivalent of the French region of Gironde. The decline of water leaves nourishing deposits in the plains and brings tonnes of various species of fish and birds. This natural event was often considered a magical recurring episode. It is celebrated in Phnom Penh during the Bon Om Touk, the Cambodian Water & Moon Festival, taking place in November, sometimes ending in late October. It is marked by three days of festive celebrations, with firework displays, concerts and boat races.

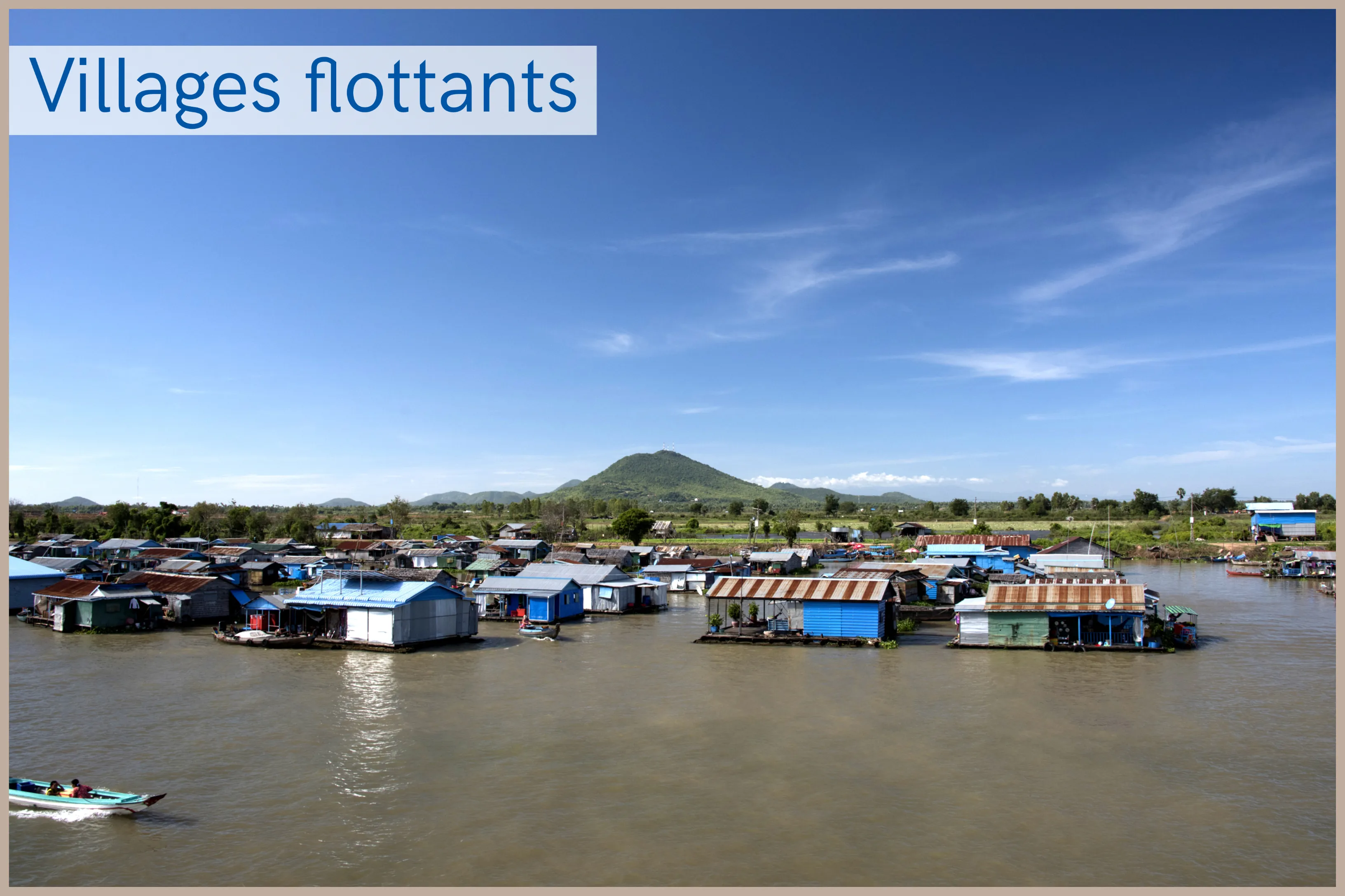

On Tonlé Sap, life is organised around the river and its temperamental nature. Stilt houses raised on piles over the surface of the water make water villages, with a combination of bamboo constructions of every size, connected to each other. Floating shops, police stations, garages and schools are all part of these towns and villages floating on the almighty water. The late French author and former Cochinchina administrator, Loÿs Pétillot, described in his poetry the fishing boats’ comings and goings, the women in multicoloured scarves, the children and their cheerful faces on their way to the nearby markets. The writer also described the sampans criss-crossing the river, the workers, male and female, of every ethnicity shouting out in various languages the contents of their packed floating shop. This is a land where old ladies still chew betel quid, palm wine makers get drunk on palm wine, and the children sleep nonchalantly in their hammocks.

The sun is rising, the water delicately dancing. The picture is just wonderful. “The more we get to know this country, the more we fall in love with it,” whispers Chhayabong, moved by so much beauty.

It is now time to leave the Indochine II in order to pursue our voyage on board a speed boat, its long nose zooming at full speed on Tonlé Sap, heading to Siem Reap, four hours away on the other side of the lake. In this city, whose name recalls the battle the Khmer army won against the Siam army (Thailand’s former name), and which favours dollars over riel, the local currency, the contrast is startling. Here, no wooden houses and ox carts can be seen, but huge palaces, trendy restaurants and gleaming fast cars.

The relatively recent opening of the nearby Angkor temples gave a spectacular boost to the tourism industry, a true economic boon for the city and the entire country.

Siem Reap, twinned with the city of Fontainebleau in France, has an international airport, a Charles de Gaulle Avenue, a catering and hospitality school, four 18-hole golf courses and a Hard Rock Café. In the evening, walking distance from the opulent covered market, the aptly-named Pub Street’s shops are all lit up, giving it the appearance of a “little Piccadilly”, the centre of a lively nightlife.

But far away from the house music and the mojito cocktails, the city has preserved its soul, its identity and its traditions, with numerous traditional workers modelling clay, working silk and stone, creating wooden sculptures, working brass, and making baskets. Trained in specialised workshops open to visitors, they have inherited a centuries-old craft from their proud ancestors. Almost 10 centuries ago, the same ancestors founded in the nearby jungle one of the world’s first and most prodigious architectural complexes.

Written by Thierry Hubac